Category Archives: Application Mgmt

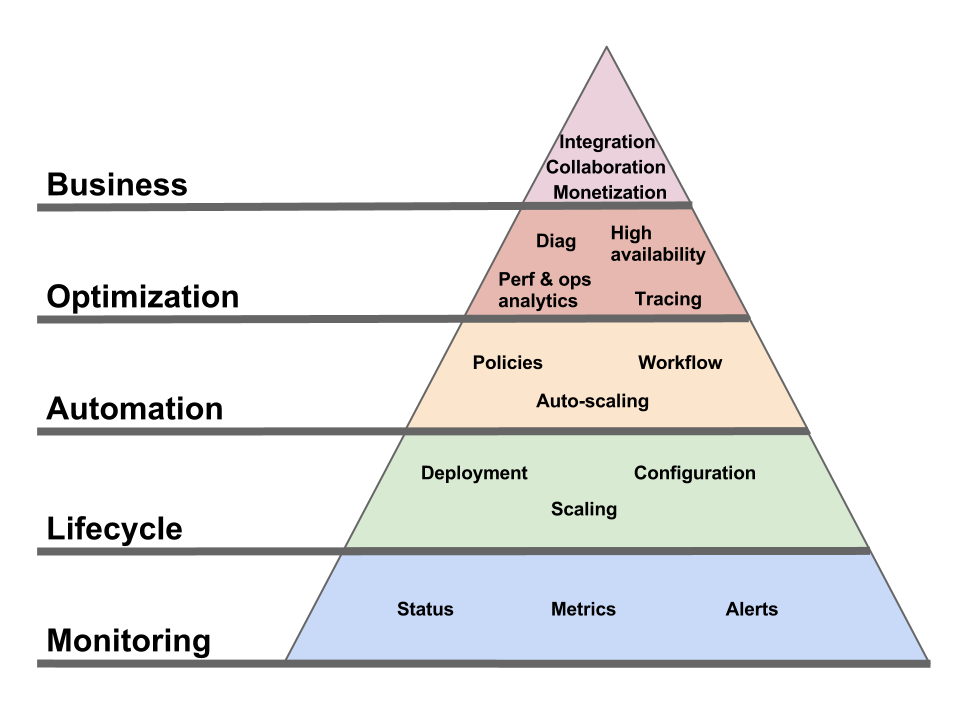

Pyramid of needs for Cloud management

Comments Off on Pyramid of needs for Cloud management

Filed under Application Mgmt, Automation, Business, Cloud Computing, Everything, Governance, IT Systems Mgmt, Manageability, Utility computing

GAE Traffic Splitting

Interesting addition to the Google App Engine (GAE) platform in release 1.6.3: Traffic Splitting lets you run several versions of your application (using a DNS sub-domain for each version) and choose to direct a certain percentage of requests to a specific version. This lets you, among other things, slowly phase in your updates and test the result on a small set of users.

That’s nice, but until I read the documentation for the feature I had assumed (and hoped) it was something else.

Rather than using traffic splitting to test different versions of my app (something which the platform now makes convenient but which I could have implemented on my own), it would be nice if that mechanism could be used to test updates to the GAE platform itself. As described in “Come for the PaaS Functional Model, stay for the Cloud Operational Model“, it’s wishful thinking to assume that changes to the PaaS platform (an update applied by Google admins) cannot have a negative effect on your application. In other words, “When NoOps meets Murphy’s Law, my money is on Murphy“.

What would be nice is if Google could give application owners advanced warning of a platform change and let them use the Traffic Splitting feature to direct a portion of the incoming requests to application instances running on the new platform. And also a way to include the platform version in all log messages.

Here’s the issue as I described it in the aforementioned “Cloud Operational Model” post:

In other words, if a patch or update is worth testing in a staging environment if you were to apply it on-premise, what makes you think that it’s less likely to cause a problem if it’s the Cloud provider who rolls it out? Sure, in most cases it will work just fine and you can sing the praise of “NoOps”. Until the day when things go wrong, your users are affected and you’re taken completely off-guard. Good luck debugging that problem, when you don’t even know that an infrastructure change is being rolled out and when it might not even have been rolled out uniformly across all instances of your application.

How is that handled in your provider’s Operational Model? Do you have visibility into the change schedule? Do you have the option to test your application on the new infrastructure or to at least influence in any way how and when the change gets rolled out to your instances?

Hopefully, the addition of Traffic Splitting to Google App Engine is a step towards addressing that issue.

Filed under Application Mgmt, Automation, Cloud Computing, DevOps, Everything, Google, Google App Engine, Utility computing

Come for the PaaS Functional Model, stay for the Cloud Operational Model

The Functional Model of PaaS is nice, but the Operational Model matters more.

Let’s first define these terms.

The Functional Model is what the platform does for you. For example, in the case of AWS S3, it means storing objects and making them accessible via HTTP.

The Operational Model is how you consume the platform service. How you request it, how you manage it, how much it costs, basically the total sum of the responsibility you have to accept if you use the features in the Functional Model. In the case of S3, the Operational Model is made of an API/UI to manage it, a bill that comes every month, and a support channel which depends on the contract you bought.

The Operational Model is where the S (“service”) in “PaaS” takes over from the P (“platform”). The Operational Model is not always as glamorous as new runtime features. But it’s what makes Cloud Cloud. If a provider doesn’t offer the specific platform feature your application developers desire, you can work around it. Either by using a slightly-less optimal approach or by building the feature yourself on top of lower-level building blocks (as Netflix did with Cassandra on EC2 before DynamoDB was an option). But if your provider doesn’t offer an Operational Model that supports your processes and business requirements, then you’re getting a hipster’s app server, not a real PaaS. It doesn’t matter how easy it was to put together a proof-of-concept on top of that PaaS if using it in production is playing Russian roulette with your business.

If the Cloud Operational Model is so important, what defines it and what makes a good Operational Model? In short, the Operational Model must be able to integrate with the consumer’s key processes: the business processes, the development processes, the IT processes, the customer support processes, the compliance processes, etc.

To make things more concrete, here are some of the key aspects of the Operational Model.

Deployment / configuration / management

I won’t spend much time on this one, as it’s the most understood aspect. Most Clouds offer both a UI and an API to let you provision and control the artifacts (e.g. VMs, application containers, etc) via which you access the PaaS functional interface. But, while necessary, this API is only a piece of a complete operational interface.

Support

What happens when things go wrong? What support channels do you have access to? Every Cloud provider will show you a list of support options, but what’s really behind these options? And do they have the capability (technical and logistical) to handle all your issues? Do they have deep expertise in all the software components that make up their infrastructure (especially in PaaS) from top to bottom? Do they run their own datacenter or do they themselves rely on a customer support channel for any issue at that level?

SLAs

I personally think discussions around SLAs are overblown (it seems like people try to reduce the entire Cloud Operational Model to a provisioning API plus an SLA, which is comically simplistic). But SLAs are indeed part of the Operational Model.

Infrastructure change management

It’s very nice how, in a PaaS setting, the Cloud provider takes care of all change management tasks (including patching) for the infrastructure. But the fact that your Cloud provider and you agree on this doesn’t neutralize Murphy’s law any more than me wearing Michael Jordan sneakers neutralizes the law of gravity when I (try to) dunk.

In other words, if a patch or update is worth testing in a staging environment if you were to apply it on-premise, what makes you think that it’s less likely to cause a problem if it’s the Cloud provider who rolls it out? Sure, in most cases it will work just fine and you can sing the praise of “NoOps”. Until the day when things go wrong, your users are affected and you’re taken completely off-guard. Good luck debugging that problem, when you don’t even know that an infrastructure change is being rolled out and when it might not even have been rolled out uniformly across all instances of your application.

How is that handled in your provider’s Operational Model? Do you have visibility into the change schedule? Do you have the option to test your application on the new infrastructure or to at least influence in any way how and when the change gets rolled out to your instances?

Note: I’ve covered this in more details before and so has Chris Hoff.

Diagnostic

Developers have assembled a panoply of diagnostic tools (memory/thread analysis, BTM, user experience, logging, tracing…) for the on-premise model. Many of these won’t work in PaaS settings because they require a console on the local machine, or an agent, or a specific port open, or a specific feature enabled in the runtime. But the need doesn’t go away. How does your PaaS Operational Model support that process?

Customer support

You’re a customer of your Cloud, but you have customers of your own and you have to support them. Do you have the tools to react to their issues involving your Cloud-deployed application? Can you link their service requests with the related actions and data exposed via your Cloud’s operational interface?

Security / compliance

Security is part of what a Cloud provider has to worry about. The problem is, it’s a very relative concept. The issue is not what security the Cloud provider needs, it’s what security its customers need. They have requirements. They have mandates. They have regulations and audits. In short, they have their own security processes. The key question, from their perspective, is not whether the provider’s security is “good”, but whether it accommodates their own security process. Which is why security is not a “trust us” black box (I don’t think anyone has coined “NoSec” yet, but it can’t be far behind “NoOps”) but an integral part of the Cloud Operational Model.

Business management

The oft-repeated mantra is that Cloud replaces capital expenses (CapExp) with operational expenses (OpEx). There’s a lot more to it than that, but it surely contributes a lot to OpEx and that needs to be managed. How does the Cloud Operational Model support this? Are buyer-side roles clearly identified (who can create an account, who can deploy a service instance, who can manage a deployed instance, etc) and do they map well to the organizational structure of the consumer organization? Can charges be segmented and attributed to various cost centers? Can quotas be set? Can consumption/cost projections be run?

We all (at least those of us who aren’t accountants) love a great story about how some employee used a credit card to get from the Cloud something that the normal corporate process would not allow (or at too high a cost). These are fun for a while, but it’s not sustainable. This doesn’t mean organizations will not be able to take advantage of the flexibility of Cloud, but they will only be able to do it if the Cloud Operational Model provides the needed support to meet the requirements of internal control processes.

Conclusion

Some of the ways in which the Cloud Operational Model materializes can be unexpected. They can seem old-fashioned. Let’s take Amazon Web Services (AWS) as an example. When they started, ownership of AWS resources was tied to an individual user’s Amazon account. That’s a big Operational Model no-no. They’ve moved past that point. As an illustration of how the Operational Model materializes, here are some of the features that are part of Amazon’s:

- You can Fedex a drive and have Amazon load the data to S3.

- You can optimize your costs for flexible workloads via spot instances.

- The monitoring console (and API) will let you know ahead of time (when possible) which instances need to be rebooted and which will need to be terminated because they run on a soon-to-be-decommissioned server. Now you could argue that it’s a limitation of the AWS platform (lack of live migration) but that’s not the point here. Limitations exists and the role of the Operational Model is to provide the tools to handle them in an acceptable way.

- Amazon has a program to put customers in touch with qualified System Integrators.

- You can use your Amazon support channel for questions related to some 3rd party software (though I don’t know what the depth of that support is).

- To support your security and compliance requirements, AWS support multi-factor authentication and has achieved some certifications and accreditations.

- Instance status checks can help streamline your diagnostic flows.

These Operational Model features don’t generate nearly as much discussion as new Functional Model features (“oh, look, a NoSQL AWS service!”) . That’s OK. The Operational Model doesn’t seek the limelight.

Business applications are involved, in some form, in almost every activity taking place in a company. Those activities take many different forms, from a developer debugging an application to an executive examining operational expenses. The PaaS Operational Model must meet their needs.

Everything is PaaSible

That’s the title of an article I wrote for InfoQ and which went live today.

If you can get past the punny title you’ll read about the following points:

- In traditional (and IaaS) environments, many available application infrastructure features remain rarely used because of the cost (perceived or real) or adding them to the operational environment.

- Most PaaS environments of today don’t even let you make use of these features, at any cost, because of constraints imposed by PaaS providers for the sake of simplifying and streamlining their operations.

- In the future, PaaS will not only make these available but available at a negligible incremental operational cost.

- Even beyond that, PaaS will make available application services that are, in traditional settings, completely out of scope for the application programmer. Early examples include CDN, DNS and loab balancing services offered, for example, by Amazon. An application developer in most traditional data centers would have to jump through endless hoops if she wanted to control these services within the application. I believe that these network-related services are just the low hanging fruits and many more once-unthinkable infrastructure services will become programmable as part of the application.

PaaS will become less about “hosting” and more about offering application services. In other words, going back to the formula I proposed on Twitter:

Cloud = Hosting + SOA

IaaS is a lot more “hosting” than SOA, PaaS is a lot more “SOA” (application infrastructure services available via APIs) than “hosting”.

You can read the full article for more.

Comments Off on Everything is PaaSible

Filed under API, Application Mgmt, Articles, Cloud Computing, Everything, Manageability, Mgmt integration, Middleware, PaaS, Utility computing

Introducing Enterprise Manager Cloud Control 12c

Oracle Enterprise Manager Cloud Control 12c, the new version of Oracle’s IT management product came out a few weeks ago, during Open World (video highlights of the launch). That release was known internally for a while as “NG” for “next generation” because the updates it contains are far more numerous and profound than your average release. The design for “NG” (now “12c”) started long before Enterprise Manager Grid Control 11g, the previous major release, shipped. The underlying framework has been drastically improved, from the modeling capabilities, to extensibility, scalability, incident management and, most visibly, UI.

If you’re not an existing EM user then those framework upgrades won’t be as visible to you as the feature upgrades and additions. And there are plenty of those as well, from database management to application management and configuration management. The most visible addition is the all-new self-service portal through which an EM-driven private Cloud can be made available. This supports IaaS-level services (individual VMs or assemblies composed of multiple coordinated VMs) and DBaaS services (we’ve also announced and demonstrated upcoming PaaS services). And it’s not just about delivering these services via lifecycle automation, a lot of work has also gone into supporting the business and organizational aspects of delivering services in a private Cloud: quotas, chargeback, cost centers, maintenance plans, etc…

EM Cloud Control is the first Oracle product with the “12c” suffix. You probably guessed it, the “c” stands for “Cloud”. If you consider the central role that IT management software plays in Cloud Computing I think it’s appropriate for EM to lead the way. And there’s a lot more “c” on the way.

Many (short and focused) demo videos are available. For more information, see the product marketing page, the more technical overview of capabilities or the even more technical product documentation. Or you can just download the product (or, for production systems, get it on eDelivery).

If you missed the launch at Open World, EM12c introduction events are taking place all over the world in November and December. They start today, November 3rd, in Athens, Riga and Beijing.

We’re eager to hear back from users about this release. I’ve run into many users blogging about installing EM12c and I’ll keep eye out for their reports after using it for a bit.

Comments Off on Introducing Enterprise Manager Cloud Control 12c

Filed under Application Mgmt, Cloud Computing, Everything, IT Systems Mgmt, Oracle, Utility computing

DMTF publishes draft of Cloud API

Note to anyone who still cares about IaaS standards: the DMTF has published a work in progress.

There was a lot of interest in the topic in 2009 and 2010. Some heated debates took place during Cloud conferences and a few symposiums were organized to try to coordinate various standard efforts. The DMTF started an “incubator” on the topic. Many companies brought submissions to the table, in various levels of maturity: VMware, Fujitsu, HP, Telefonica, Oracle and RedHat. IBM and Microsoft might also have submitted something, I can’t remember for sure.

The DMTF has been chugging along. The incubator turned into a working group. Unfortunately (but unsurprisingly), it limited itself to the usual suspects (and not all the independent Cloud experts out there) and kept the process confidential. But this week it partially lifted the curtain by publishing two work-in-progress documents.

They can be found at http://dmtf.org/standards/cloud but if you read this after March 2012 they won’t be there anymore, as DMTF likes to “expire” its work-in-progress documents. The two docs are:

- Cloud Infrastructure Management Interface (CIMI) Model and REST Interface Specification, and

- Cloud Infrastructure Management Interface – Common Information Model (CIMI-CIM) Specification

The first one is the interesting one, and the one you should read if you want to see where the DMTF is going. It’s a RESTful specification (at the cost of some contortions, e.g. section 4.2.1.3.1). It supports both JSON and XML (bad idea). It plans to use RelaxNG instead of XSD (good idea). And also CIM/MOF (not a joke, see the second document for proof). The specification is pretty ambitious (it covers not just lifecycle operations but also monitoring and events) and well written, especially for a work in progress (props to Gil Pilz).

I am surprised by how little reaction there has been to this publication considering how hotly debated the topic used to be. Why is that?

A cynic would attribute this to people having given up on DMTF providing a Cloud API that has any chance of wide adoption (the adjoining CIM document sure won’t help reassure DMTF skeptics).

To the contrary, an optimist will see this low-key publication as a sign that the passions have cooled, that the trusted providers of enterprise software are sitting at the same table and forging consensus, and that the industry is happy to defer to them.

More likely, I think people have, by now, enough Cloud experience to understand that standardizing IaaS APIs is a minor part of the problem of interoperability (not to mention the even harder goal of portability). The serialization and plumbing aspects don’t matter much, and if they do to you then there are some good libraries that provide mappings for your favorite language. What matters is the diversity of resources and services exposed by Cloud providers. Those choices strongly shape the design of your application, much more than the choice between JSON and XML for the control API. And nobody is, at the moment, in position to standardize these services.

So congrats to the DMTF Cloud Working Group for the milestone, and please get the API finalized. Hopefully it will at least achieve the goal of narrowing down the plumbing choices to three (AWS, OpenStack and DMTF). But that’s not going to solve the hard problem.

BSM with Oracle Enterprise Manager 11g

My colleagues Ashwin Karkala and Govinda Sambamurthy have written a book about modeling and managing business services using the current version of Enterprise Manager Grid Control (11g R1). Nobody would have been better qualified for this task since they built a lot of the features they describe. I acted as a technical reviewer for this book and very much enjoyed reading it in the process.

Whether you are a current EM user who wants to make sure you know and use the BSM features or someone just considering EM for that task, this is the book you want.

The full title is Oracle Enterprise Manager Grid Control 11g R1: Business Service Management.

As a bonus feature, and for a limited time only, if you purchase this book over the next 48 hours you get to follow the authors, @ashwinkarkala and @govindars on Twitter at no extra cost! A $2,000 value (at least).

Comments Off on BSM with Oracle Enterprise Manager 11g

Filed under Application Mgmt, Book review, BSM, Everything, IT Systems Mgmt, Mgmt integration, Modeling, Oracle, People

AJAX+REST as the latest architectural mirage

If the Web wasn’t tragically amnesic, I could show you 15-year old articles explaining how XSLT was about to revolutionize Web applications. In that vision, your Web server would return an XML file with all the data; and alongside that XML, an XSLT (which describes how to transform the XML into HTML). The browser would run it on the XML data and display the resulting HTML. Voila! This was going to bring all kinds of benefits over the old server-spits-out-HTML model. The XML could be easily consumed by other applications (not just humans) and different XSLTs could be used to adapt to the various client platforms.

This hasn’t panned out. At least not in that form. Enters AJAX. The XML doc is still there, though it usually wants to be called JSON. The XSLT is now a big pile of JavaScript. That model has many advantages over the XSLT model, the first one being that you don’t have to use XSLT (and I’m talking as someone who actually enjoys XPath). It’s a lot more flexible, you can do small updates and partial page refresh, etc. But does it also maintain the architectural cleanliness of having a data API separated from the rendering logic?

Sometimes. Lori MacVittie describes that model. That’s how the cool kids do it and they make sure to repeat in every sentence that their Web app uses the same API as 3rd party apps. The Twitter web app, for example, is in this category, as Mike Loukides describes. As is Apache Orion (the diagram below comes from the Orion architecture)

That’s one model, and it is conceptually very elegant. One API, many consumers. The Web site of the service provider is just another consumer. Easy versioning. An application management dream (one API to manage, a well-defined set of operations and flows to test, trace and diagnose). From a security perspective, it offers the smallest possible attack surface. Easy interoperability between different applications consuming the same API. All goodies.

And not just theoretical goodies, there are situations where it is the right model.

And yet I am still dubious that it’s going to be the dominant model. Clients of the same service support different interaction models and it’s hard for a single API to work well for all without sprawling out of control (to the point where calling it “one API” becomes a fig leaf). But if you want to keep the API surface small, you might end up with chatty apps. Not to mention the temptation for service providers to give their software special access over those of their partners/competitors (e.g. other Twitter clients).

Take Google+. As of this writing, the web site is up and obviously very AJAX-driven. And yet the API is not available. There maybe non-technical reasons for it, but if the Google+ web site was just another consumer of the API then wouldn’t, by definition, the API already be up?

The decision of whether to expose the interface consumed by your AJAX app as an open API also has ramifications in the implementation strategy. Such an approach pretty much rules out using frameworks that integrate server-side and browser-side development and pushes you towards writing them separately (and thus controlling all the details of how they interact so that you can make sure it happens in a way that’s consumable by 3rd parties). Though the reverse is not true. You may decide that you don’t want that API exposed to 3rd parties and yet still manually define it and keep your server-side and browser-side code at arms length.

If you decide to go the “one REST API for all” route and forgo frameworks that integrate browser code and server code, how much are you leaving on the table? After all, preeminent developers love to sneer at such frameworks. But that’s a short-sighted view.

Some tennis players think of their racket as one tool. Others, who own a stringing machine, think of the frame and the string as two tools, that they expertly combine. Similarly, not all Web developers want to think of their client framework and their server framework as two tools. Using them as one, pre-assembled, tool may not provide the most optimal code, but may still be the optimal use of your development resources.

There’s a bit of Ricardian angle to this. Even if you can produce better JavaScript (by “better” I mean better suited to your need) than the framework, you have a higher Comparative Advantage in developing business logic than JavaScript so you should focus your efforts there and “import” the JavaScript from the framework (which is utterly incompetent in creating business logic).

Just like, in Ricardo’s famous example, Portugal is better off importing its cloth from England (and focusing on producing wine) even though it is, in absolute term, more able to produce cloth than England is.

Which contradicts Matt Raible’s statement that “the only people that like Ajax integrated into their web frameworks are programmers scared of JavaScript (who probably shouldn’t be developing your UI).” His characterization is sometimes correct, but not absolute as he asserts.

I wouldn’t write Google+ with ADF, but it provides benefits to large class of applications, especially internal applications. Where you’re willing to give away some design control for the benefit of faster development and better-tested JavaScript.

Then there is the orthogonal question of whether AJAX technologies are well-suited to a RESTful architecture. You may think it’s obvious, since both are natively designed for the Web. But a wine glass and a steering wheel are both natively designed for the human hand; that doesn’t make them a good pair. Here’s one way to plant doubt in your mind: if AJAX was a natural fit for REST, would we need the atrocity known as the hashbang? Would AJAX applications need to be made crawlable? Reuven Cohen asserts that “AJAX is quite possibly the worst way to consume a RESTful API”, but unfortunately he doesn’t develop the demonstration. Maybe a topic for a future post.

“Because that’s the way it’s done now” was a bad reason to transform perfectly-functional XML-RPC into “message-oriented” SOAP. It also is a bad reason for assuming that your Web application needs to be AJAX-on-REST.

I’ll leave the last word to Stefan Tilkov: “Don’t confuse integration architecture with application architecture.” His talk doesn’t focus on how to build Web UIs, but the main lesson applies. Here’s the video and here are the slides (warning: Flash and PDF, respectively, which is sadly ironic for such a good presentation about Web technology).

Filed under API, Application Mgmt, Everything, JavaScript, Middleware, Mobile, Protocols, REST, Tech, Web services

Reading IBM’s proposed standard for Cloud Architecture

Did you enjoy the first version of IBM’s Cloud Computing Reference Architecture? Did you even get certified on it? Then rejoice, because there’s a new version. IBM recently submitted the IBM Cloud Computing Reference Architecture 2.0 to The Open Group.

I’m a bit out of practice reading this kind of IBMese (let’s just say that The Open Group was the right place to submit it) but I would never let my readers down. So, even though these box-within-a-box-within-a-box diagrams (see section 2) give me flashbacks to the days of OGF and WSRF, I soldiered on.

I didn’t understand the goal of the document enough to give you a fair summary, but I can share some thoughts.

It starts by talking a lot about SOA. I initially thought this was to make the point that Glen Daniels articulated very well in this tweet:

Yup, correct SOA patterns (loose coupling, dyn refs, coarse interfaces…) are exactly what you need for cloud apps. You knew this.

But no. Rather than Glen’s astute remark, IBM’s point is one meta-level lower. It’s that “Cloud solutions are SOA solutions”. Which I have a harder time parsing. If you though “service” was overloaded before…

While some of the IBM authors are SOA experts, others apparently come from a Telco background so we get OSS/BSS analogies next.

By that point, I’ve learned that Cloud is like SOA except when it’s like Telco (but there’s probably another reference architecture somewhere that explains that Telco is SOA, so it all adds up).

One thing that chagrined me was that even though this document is very high-level it still manages to go down into implementatin technologies long enough to assert, wrongly, that virtualization is required for Cloud solutions. Another Cloud canard repeated here is the IaaS/PaaS/SaaS segmentation of the Cloud world, to which IBM adds a BPaaS (Business Process as a Service) layer for good measure (for my take on how Cloud relates to SOA, and how I dislike the IaaS/PaaS/SaaS pyramid, see this write-up of the presentation I gave at last year’s Cloud Connect, especially the 3rd picture).

It gets a lot better if you persevere to page 29, where the “Architecture Principles” finally get introduced (if had been asked to edit the paper, I would have only kept the last 6 pages). They are:

- Design for Cloud-scale Efficiencies: When realizing cloud characteristics such as elasticity, self-service access, and flexible sourcing, the cloud design is strictly oriented to high cloud scale efficiencies and short time-to-delivery/time-to-change. (“Efficiency Principle”)

- Support Lean Service Management: The Common Cloud Management Platform fosters lean and lightweight service management policies, processes, and technologies. (“Lightweightness Principle”)

- Identify and Leverage Commonalities: All commonalities are identified and leveraged in cloud service design. (“Economies-of-scale principle”)

- Define and Manage generically along the Lifecycle of Cloud Services: Be generic across I/P/S/BPaaS & provide ‘exploitation’ mechanism to support various cloud services using a shared, common management platform (“Genericity”).

Each principle gets a nickname, thanks to which IBM can refer to this list as the ELEG principles (Efficiency, Lightweightness, Economies-of-scale, Genericity). It also spells GLEE, but apparently that’s wasn’t the prefered sequence.

The first principle is hard to disagree with. The second also rings true, including its dings on ITIL (but the irony of IBM exhaulting “Lightweightness” is hard to ignore). The third and fourth principles (by that time I had lost too many brain cells to understand how they differ) really scared me. While I can understand the motivation, they elicited a vision of zombies in blue suits (presumably undead IBM Distinguish Engineers and Fellows) staggering towards me: “frameworks… we want frameworks…”.

There you go. If you want more information (and, more importantly, unbiased information) go read the Reference Architecture yourself. I am not involved in The Open Group, and I have no idea what it plans to do with it (and if it has received other submissions of the same type). Though I wouldn’t be surprised if I see, in 5 years, some panic sales rep asking an internal mailing list “The customer RPF asks for a mapping of our solution to the Open Group Cloud Reference Architecture and apparently IBM has 94 slides about it, what do I do? Has anyone heard about this Reference Architecture? This is urgent.”

Urgent things are long in the making.

CloudFormation in context

I’ve been very positive about AWS CloudFormation (both in tweet and blog form) since its announcement . I want to clarify that it’s not the technology that excites me. There’s nothing earth-shattering in it. CloudFormation only covers deployment and doesn’t help you with configuration, monitoring, diagnostic and ongoing lifecycle. It’s been done before (including probably a half-dozen times within IBM alone, I would guess). We’ve had much more powerful and flexible frameworks for a long time (I can’t even remember when SmartFrog first came out). And we’ve had frameworks with better tools (though history suggests that tools for CloudFormation are already in the works, not necessarily inside Amazon).

Here are some non-technical reasons why I tweeted that “I have a feeling that the AWS CloudFormation format might become an even more fundamental de-facto standard than the EC2 API” even before trying it out.

It’s simple to use. There are two main reasons for this (and the fact that it uses JSON rather than XML is not one of them):

– It only support a small set of features

– It “hard-codes” resource types (e.g. EC2, Beanstalk, RDS…) rather than focusing on an abstract and extensible mechanism

It combines a format and an API. You’d think it’s obvious that the two are complementary. What can you do with a format if you don’t have an API to exchange documents in that format? Well, turns out there are lots of free-floating model formats out there for which there is no defined API. And they are still wondering why they never saw any adoption.

It merges IaaS and PaaS. AWS has always defied the “IaaS vs. PaaS” view of the Cloud. By bridging both, CloudFormation is a great way to provide a smooth transition. I expect most of the early templates to be very EC2-centric (are as most AWS deployments) and over time to move to a pattern in which EC2 resources are just used for what doesn’t fit in more specialized containers).

It comes at the right time. It picks the low-hanging fruits of the AWS automation ecosystem. The evangelism and proof of concept for templatized deployments have already taken place.

It provides a natural grouping of the various AWS resources you are currently consuming. They are now part of an explicit deployment context.

It’s free (the resources provisioned are not free, of course, but the fact that they came out of a CloudFormation deployment doesn’t change the cost).

Comments Off on CloudFormation in context

Filed under Amazon, Application Mgmt, Automation, Cloud Computing, Everything, Mgmt integration, Modeling, PaaS, Specs, Utility computing

AWS CloudFormation is the iPhone of Cloud services

Expanding on tweet that I wrote soon after the announcement of AWS CloudFormation.

The iPhone unifies the GPS, phone, PDA, camera and camcorder. CloudFormation does the same for infrastructure services (VMs, volumes, network…) and some platform services (Beanstalk, RDS, SimpleDB, SQS, SNS…). You don’t think about whether you should grab a phone or a PDA, you grab an iPhone and start using the feature you need. It’s the default tool. Similarly with CloudFormation, you won’t start by thinking about what AWS service you want to use. Rather, you grab a CloudFormation template and modify it as needed. The template (or the template editor) is the default tool.

The iPhone doesn’t just group features that used to be provided by many devices. It also allows these features to collaborate. It’s not that you get a PDA and a phone side-by-side in one device. You can press the “call” button from the “PDA” feature. CloudFormation doesn’t just bundle deployments to various AWS services, it wires them together.

Anyone can write apps for the iPhone. Anyone can write apps that use CloudFormation.

There’s an App Store for iPhone apps. On the CloudFormation side, it will probably come soon (right now Amazon has made templates available on S3, but that’s not a real store). Amazon has developed example templates for a set of common applications, but expect application authors to take ownership of that task soon. They’ll consider it one of their deliverables. Right next to the “download” button you’ll start seeing a “deploy to AWS” button. Guess which one will eventually be used the most?

It’s Apple’s platform and your applications have to comply with their policy. AWS is not as much of a control freak as Apple and doesn’t have an upfront approval process, but it has its terms of service and they too can get you kicked out.

The iPhone is not a standard platform (though you may consider it a de-facto standard). Same for AWS CloudFormation.

There are alternatives to the iPhone that define themselves primarily as being more open than it, mainly Android. Same for AWS with OpenStack (which probably will soon have its CloudFormation equivalent).

The iPhone infiltrated itself into corporations at the ground level, even if the CIO initially saw no reason to look beyond BlackBerry for corporate needs. Same with AWS.

Any other parallel? Any fundamental difference I missed?

The REST bubble

Just yesterday I was writing about how Cloud APIs are like military parades. To some extent, their REST rigor is a way to enforce implementation discipline. But a large part of it is mostly bling aimed at showing how strong (for an army) or smart (for an API) the people in charge are.

Case in point, APIs that have very simple requirements and yet make a big deal of the fact that they are perfectly RESTful.

Just today, I learned (via the ever-informative InfoQ) about the JBoss SteamCannon project (a PaaS wrapper for Java and Ruby apps that can deploy on different host infrastructures like EC2 and VirtualBox). The project looks very interesting, but the API doc made me shake my head.

The very first thing you read is three paragraphs telling you that the API is fully HATEOS (Hypermedia as the Engine of Application State) compliant (our URLs are opaque, you hear me, opaque!) and an invitation to go read Roy’s famous take-down of these other APIs that unduly call themselves RESTful even though they don’t give HATEOS any love.

So here I am, a developer trying to deploy my WAR file on SteamCannon and that’s the API document I find.

Instead of the REST finger-wagging, can I have a short overview of what functions your API offers? Or maybe an example of a request call and its response?

I don’t mean to pick on SteamCannon specifically, it just happens to be a new Cloud API that I discovered today (all the Cloud API out there also spend too much time telling you how RESTful they are and not enough time showing you how simple they are). But when an API document starts with a REST lesson and when PowerPoint-waving sales reps pitch “RESTful APIs” to executives you know this REST thing has gone way beyond anything related to “the fundamentals”.

We have a REST bubble on our hands.

Again, I am not criticizing REST itself. I am criticizing its religious and ostentatious application rather than its practical use based on actual requirements (this was my take on its practical aspects in the context of Cloud APIs).

Filed under API, Application Mgmt, Cloud Computing, Everything, JBoss, Mgmt integration, Protocols, REST, Utility computing

Amazon proves that REST doesn’t matter for Cloud APIs

Every time a new Cloud API is announced, its “RESTfulness” is heralded as if it was a MUST HAVE feature. And yet, the most successful of all Cloud APIs, the AWS API set, is not RESTful.

We are far enough down the road by now to conclude that this isn’t a fluke. It proves that REST doesn’t matter, at least for Cloud management APIs (there are web-scale applications of an entirely different class for which it does). By “doesn’t matter”, I don’t mean that it’s a bad choice. Just that it is not significantly different from reasonable alternatives, like RPC.

AWS mostly uses RPC over HTTP. You send HTTP GET requests, with instructions like ?Action=CreateKeyPair added in the URL. Or DeleteKeyPair. Same for any other resource (volume, snapshot, security group…). Amazon doesn’t pretend it’s RESTful, they just call it “Query API” (except for the DevPay API, where they call it “REST-Query” for unclear reasons).

Has this lack of REStfulness stopped anyone from using it? Has it limited the scale of systems deployed on AWS? Does it limit the flexibility of the Cloud offering and somehow force people to consume more resources than they need? Has it made the Amazon Cloud less secure? Has it restricted the scope of platforms and languages from which the API can be invoked? Does it require more experienced engineers than competing solutions?

I don’t see any sign that the answer is “yes” to any of these questions. Considering the scale of the service, it would be a multi-million dollars blunder if indeed one of them had a positive answer.

Here’s a rule of thumb. If most invocations of your API come via libraries for object-oriented languages that more or less map each HTTP request to a method call, it probably doesn’t matter very much how RESTful your API is.

The Rackspace people are technically right when they point out the benefits of their API compared to Amazon’s. But it’s a rounding error compared to the innovation, pragmatism and frequency of iteration that distinguishes the services provided by Amazon. It’s the content that matters.

If you think it’s rich, for someone who wrote a series of post examining “REST in practice for IT and Cloud management” (part 1, part 2 and part 3), to now declare that REST doesn’t matter, well go back to these posts. I explicitly set them up as an effort to investigate whether (and in what way) it mattered and made it clear that my intuition was that actual RESTfulness didn’t matter as much as simplicity. The AWS API being an example of the latter without the former. As I wrote in my review of the Sun Cloud API, “it’s not REST that matters, it’s the rest”. One and a half years later, I think the case is closed.

Filed under Amazon, Application Mgmt, Cloud Computing, Everything, Implementation, Mgmt integration, REST, Specs, Utility computing

Nice incremental progress in Google App Engine SDK 1.4

When Google released version 1.3.8 of the Google App Engine SDK in October, they introduced an instance console, showing you how many instances are serving your application and some basic metrics about these instances. I wrote a blog to consider the implications of providing this level of visibility to application administrators. It also pointed out some shortcomings of this first version of the console.

The most glaring problem was that the console showed an “average latency” which was just a straight average of the latencies of all the instances, independently of the traffic they see. Which is a meaningless number.

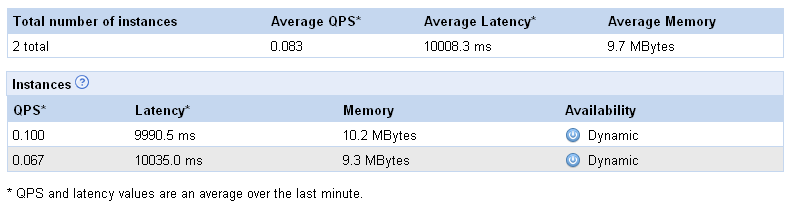

Today, Google released an update to the SDK (1.4), and along with it some minor updates to the instance console. Except that, as you can see below, the screen capture in their announcement happens to show three instances that have processed exactly the same number of messages. Which means that we can’t tell whether they have fixed the “unweighted average” problem or not. Is this just by chance? Google, WTF? (which stands for “what’s the formula?”, of course).

I decided it was worth spending a few minutes to find the answer. I don’t have any app currently in use on GAE, but it doesn’t take much work to generate enough load to wake up one of my old apps and get it to spin a couple of instances. Here is the resulting console instance:

If you run the numbers, you can see that they’ve fixed that issue; the average latency is now weighted based on instance traffic. Thanks Google for listening.

Apparently, not all the updates have trickled down to my version of the instance console. The “requests”, “errors” and “age” columns are missing. I assume they’re on their way. Seeing the age of the instances, especially, is a nice addition, one of those I requested in my blog.

In the grand scheme of things, these minor updates to the console (which remains quite basic) are not the big news. The major announcement with SDK 1.4 is that the dreaded 30 seconds limit on execution time has been lifted for background tasks (those from Task Queue and Cron). It’s now a much more manageable 10 minutes. This doesn’t apply to the execution of Web requests served by your app.

Google App Engine has been under criticism recently, and that 30-second limit (along with reliability issues) figured prominently in the complains. Assuming the reliability issues are also coming under control, this update will go a long way towards addressing these issues.

Just so you realize how lucky you are if you are just now starting with Google App Engine, here are the kind of hoops you had to jump through, in the early days, to process any task that took a significant amount of time. This was done a year before the Cron and Task Queue features were added to GAE.

Another nice addition with SDK 1.4 is that you can now retrieve the source code of your application from Google’s servers. Of course you should never need that if you are rigorous and well-organized… Presumably this is only for Python since in the Java case Google’s servers never see the source code.

The steady progress of the GAE SDK continues.

Cloud management is to traditional IT management what spreadsheets are to calculators

It’s all in the title of the post. An elevator pitch short enough for a 1-story ride. A description for business people. People who don’t want to hear about models, virtualization, blueprints and devops. But people who also don’t want to be insulted with vague claims about “business/IT alignment” and “agility”.

The focus is on repeatability. Repeatability saves work and allows new approaches. I’ve found spreadsheets (and “super-spreadsheets”, i.e. more advanced BI tools) to be a good analogy for business people. Compared to analysts furiously operating calculators, spreadsheets save work and prevent errors. But beyond these cost savings, they allow you to do things you wouldn’t even try to do without them. It’s not just the same process, done faster and cheaper. It’s a more mature way of running your business.

Same with the “Cloud” style of IT management.

Lifting the curtain on PaaS Cloud infrastructure (can you handle the truth?)

The promise of PaaS is that application owners don’t need to worry about the infrastructure that powers the application. They just provide application artifacts (e.g. WAR files) and everything else is taken care of. Backups. Scaling. Infrastructure patching. Network configuration. Geographic distribution. Etc. All these headaches are gone. Just pick from a menu of quality of service options (and the corresponding price list). Make your choice and forget about it.

In theory.

In practice no abstraction is leak-proof and the abstractions provided by PaaS environments are even more porous than average. The first goal of PaaS providers should be to shore them up, in order to deliver on the PaaS value proposition of simplification. But at some point you also have to acknowledge that there are some irreducible leaks and take pragmatic steps to help application administrators deal with them. The worst thing you can do is have application owners suffer from a leaky abstraction and refuse to even acknowledge it because it breaks your nice mental model.

Google App Engine (GAE) gives us a nice and simple example. When you first deploy an application on GAE, it is deployed as just one instance. As traffic increases, a second instance comes up to handle the load. Then a third. If traffic decreases, one instance may disappear. Or one of them may just go away for no reason (that you’re aware of).

It would be nice if you could deploy your application on what looks like a single, infinitely scalable, machine and not ever have to worry about horizontal scale-out. But that’s just not possible (at a reasonable cost) so Google doesn’t try particularly hard to hide the fact that many instances can be involved. You can choose to ignore that fact and your application will still work. But you’ll notice that some requests take a lot more time to complete than others (which is typically the case for the first request to hit a new instance). And some requests will find an empty local cache even though your application has had uninterrupted traffic. If you choose to live with the “one infinitely scalable machine” simplification, these are inexplicable and unpredictable events.

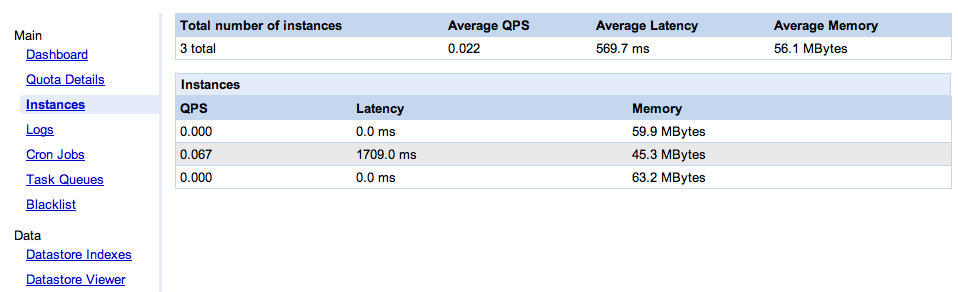

Last week, as part of the release of the GAE SDK 1.3.8, Google went one step further in acknowledging that several instances can serve your application, and helping you deal with it. They now give you a console (pictured below) which shows the instances currently serving your application.

I am very glad that they added this console, because it clearly puts on the table the question of how much your PaaS provider should open the kimono. What’s the right amount of visibility, somewhere between “one infinitely scalable computer” and giving you fan speeds and CPU temperature?

I don’t know what the answer is, but unfortunately I am pretty sure this console is not it. It is supposed to be useful “in debugging your application and also understanding its performance characteristics“. Hmm, how so exactly? Not only is this console very simple, it’s almost useless. Let me enumerate the ways.

Misleading

Actually it’s worse than useless, it’s misleading. As we can see on the screen shot, two of the instances saw no traffic during the collection period (which, BTW, we don’t know the length of), while the third one did all the work. At the top, we see an “average latency” value. Averaging latency across instances is meaningless if you don’t weight it properly. In this case, all the requests went to the instance that had an average latency of 1709ms, but apparently the overall average latency of the application is 569.7ms (yes, that’s 1709/3). Swell.

No instance identification

What happens when the console is refreshed? Maybe there will only be two instances. How do I know which one went away? Or say there are still three, how do I know these are the same three? For all I know it could be one old instance and two new ones. The single most important data point (from the application administrator’s perspective) is when a new instance comes up. I have no way, in this UI, to know reliably when that happens: no instance identification, no indication of the age of an instance.

Average memory

So we get the average memory per instance. What are we supposed to do with that information? What’s a good number, what’s a bad number? How much memory is available? Is my app memory-bound, CPU-bound or IO-bound on this instance?

Configuration management

As I have described before, change and configuration management in a PaaS setting is a thorny problem. This console doesn’t tackle it. Nowhere does it say which version of the GAE platform each instance is running. Google announces GAE SDK releases (the bits you download), but these releases are mostly made of new platform features, so they imply a corresponding update to Google’s servers. That can’t happen instantly, there must be some kind of roll-out (whether the instances can be hot-patched or need to be recycled). Which means that the instances of my application are transitioned from one platform version to another (and presumably that at a given point in time all the instances of my application may not be using the same platform version). Maybe that’s the source of my problem. Wouldn’t it be nice if I knew which platform version an instance runs? Wouldn’t it be nice if my log files included that? Wouldn’t it be nice if I could request an app to run on a specific platform version for debugging purpose? Sure, in theory all the upgrades are backward-compatible, so it “shouldn’t matter”. But as explained above, “the worst thing you can do is have application owners suffer from a leaky abstraction and refuse to even acknowledge it“.

OK, so the instance monitoring console Google just rolled out is seriously lacking. As is too often the case with IT monitoring systems, it reports what is convenient to collect, not what is useful. I’m sure they’ll fix it over time. What this console does well (and really the main point of this blog) is illustrate the challenge of how much information about the underlying infrastructure should be surfaced.

Surface too little and you leave application administrators powerless. Surface more data but no control and you’ll leave them frustrated. Surface some controls (e.g. a way to configure the scaling out strategy) and you’ve taken away some of the PaaS simplicity and also added constraints to your infrastructure management strategy, making it potentially less efficient. If you go down that route, you can end up with the other flavor of PaaS, the IaaS-based PaaS in which you have an automated way to create a deployment but what you hand back to the application administrator is a set of VMs to manage.

That IaaS-centric PaaS is a well-understood beast, to which many existing tools and management practices can be applied. The “pure PaaS” approach pioneered by GAE is much more of a terra incognita from a management perspective. I don’t know, for example, whether exposing the platform version of each instance, as described above, is a good idea. How leaky is the “platform upgrades are always backward-compatible” assumption? Google, and others, are experimenting with the right abstraction level, APIs, tools, and processes to expose to application administrators. That’s how we’ll find out.

Redeeming the service description document

A bicycle is a convenient way to go buy cigarettes. Until one day you realize that buying cigarettes is a bad idea. At which point you throw away your bicycle.

Sounds illogical? Well, that’s pretty much what the industry has done with service descriptions. It went this way: people used WSDL (and stub generation tools built around it) to build distributed applications that shared too much. Some people eventually realized that was a bad approach. So they threw out the whole idea of a service description. And now, in the age of APIs, we are no more advanced than we were 15 years ago in terms of documenting application contracts. It’s tragic.

The main fallacies involved in this stagnation are:

- Assuming that service descriptions are meant to auto-generate all-encompassing program stubs,

- Looking for the One True Description for a given service,

- Automatically validating messages based on the service description.

I’ll leave the first one aside, it’s been widely covered. Let’s drill in a bit into the other two.

There is NOT One True Description for a given service

Many years ago, in the same galaxy where we live today (only a few miles from here, actually), was a development team which had to implement a web service for a specific WSDL. They fed the WSDL to their SOAP stack. This was back in the days when WSDL interoperability was a “promise” in the “political campaign” sense of the term so of course it didn’t work. As a result, they gave up on their SOAP stack and implemented the service as a servlet. Which, for a team new to XML, meant a long delay and countless bugs. I’ll always remember the look on the dev lead’s face when I showed him how 2 minutes and a text editor were all you needed to turn the offending WSDL in to a completely equivalent WSDL (from the point of view of on-the-wire messages) that their toolkit would accept.

(I forgot what the exact issue was, maybe having operations with different exchange patterns within the same PortType; or maybe it used an XSD construct not supported by the toolkit, and it was just a matter of removing this constraint and moving it from schema to code. In any case something that could easily be changed by editing the WSDL and the consumer of the service wouldn’t need to know anything about it.)

A service description is not the literal word of God. That’s true no matter where you get it from (unless it’s hand-delivered by an angel, I guess). Just because adding “?wsdl” to the URL of a Web service returns an XML document doesn’t mean it’s The One True Description for that service. It’s just the most convenient one to generate for the app server on which the service is deployed.

One of the things that most hurts XML as an on-the-wire format is XSD. But not in the sense that “XSD is bad”. Sure, it has plenty of warts, but what really hurts XML is not XSD per se as much as the all-too-common assumption that if you use XML you need to have an XSD for it (see fat-bottomed specs, the key message of which I believe is still true even though SML and SML-IF are now dead).

I’ve had several conversations like this one:

– The best part about using JSON and REST was that we didn’t have to deal with XSD.

– So what do you use as your service contract?

– Nothing. Just a human-readable wiki page.

– If you don’t need a service contract, why did you feel like you had to write an XSD when you were doing XML? Why not have a similar wiki page describing the XML format?

– …

It’s perfectly fine to have service descriptions that are optimized to meet a specific need rather than automatically focusing on syntax validation. Not all consumers of a service contract need to be using the same description. It’s ok to have different service descriptions for different users and/or purposes. Which takes us to the next fallacy. What are service descriptions for if not syntax validation?

A service description does NOT mean you have to validate messages

As helpful as “validation” may seem as a concept, it often boils down to rejecting messages that could otherwise be successfully processed. Which doesn’t sound quite as useful, does it?

There are many other ways in which service descriptions could be useful, but they have been largely neglected because of the focus on syntactic validation and stub generation. Leaving aside development use cases and looking at my area of focus (application management), here are a few use cases for service descriptions:

Creating test messages (aka “synthetic transactions”)

A common practice in application management is to send test messages at regular intervals (often from various locations, e.g. branch offices) to measure the availability and response time of an application from the consumer’s perspective. If a WSDL is available for the service, we use this to generate the skeleton of the test message, and let the admin fill in appropriate values. Rather than a WSDL we’d much rather have a “ready-to-use” (possibly after admin review) test message that would be provided as part of the service description. Especially as it would be defined by the application creator, who presumably knows a lot more about that makes a safe and yet relevant message to send to the application as a ping.

Attaching policies and SLAs

One of the things that WSDLs are often used for, beyond syntax validation and stub generation, is to attach policies and SLAs. For that purpose, you really don’t need the XSD message definition that makes up so much of the WSDL. You really just need a way to identify operations on which to attach policies and SLAs. We could use a much simpler description language than WSDL for this. But if you throw away the very notion of a description language, you’ve thrown away the baby (a classification of the requests processed by the service) along with the bathwater (a syntax validation mechanism).

Governance / versioning

One benefit of having a service description document is that you can see when it changes. Even if you reduce this to a simple binary value (did it change since I last checked, y/n) there’s value in this. Even better if you can introspect the description document to see which requests are affected by the change. And whether the change is backward-compatible. Offering the “before” XSD and the “after” XSD is almost useless for automatic processing. It’s unlikely that some automated XSD inspection can tell me whether I can keep using my previous messages or I need to update them. A simple machine-readable declaration of that fact would be a lot more useful.

I just listed three, but there are other application management use cases, like governance/auditing, that need a service description.

In the SOAP world, we usually make do with WSDL for these tasks, not because it’s the best tool (all we really need is a way to classify requests in “buckets” – call them “operations” if you want – based on the content of the message) but because WSDL is the only understanding that is shared between the caller and the application.

By now some of you may have already drafted in your head the comment you are going to post explaining why this is not a problem if people just use REST. And it’s true that with REST there is a default categorization of incoming messages. A simple matrix with the various verbs as columns (GET, POST…) and the various resource types as rows. Each message can be unambiguously placed in one cell of this matrix, so I don’t need a service description document to have a request classification on which I can attach SLAs and policies. Granted, but keep these three things in mind:

- This default categorization by verb and resource type can be a quite granular. Typically you wouldn’t have that many different policies on your application. So someone who understands the application still needs to group the invocations into message categories at the right level of granularity.

- This matrix is only meaningful for the subset of “RESTful” apps that are truly… RESTful. Not for all the apps that use REST where it’s an easy mental mapping but then define resource types called “operations” or “actions” that are just a REST veneer over RPC.

- Even if using REST was a silver bullet that eliminated the need for service definitions, as an application management vendor I don’t get to pick the applications I manage. I have to have a solution for what customers actually do. If I restricted myself to only managing RESTful applications, I’d shrink my addressable market by a few orders of magnitude. I don’t have an MBA, but it sounds like a bad idea.

This is not a SOAP versus REST post. This is not a XML versus JSON post. This is not a WSDL versus WADL post. This is just a post lamenting the fact that the industry seems to have either boxed service definitions into a very limited use case, or given up on them altogether. It I wasn’t recovering from standards burnout, I’d look into a versatile mechanism for describing application services in a way that is geared towards message classification more than validation.

Comments Off on Redeeming the service description document

Filed under API, Application Mgmt, Everything, Governance, IT Systems Mgmt, Manageability, Mashup, Mgmt integration, Middleware, Modeling, Protocols, REST, SML, SOA, Specs, Standards

Exalogic, EC2-on-OVM, Oracle Linux: The Oracle Open World early recap

Among all the announcements at Oracle Open World so far, here is a summary of those I was the most impatient to blog about.

Oracle Exalogic Elastic Cloud

This was the largest part of Larry’s keynote, he called it “one big honkin’ cloud”. An impressive piece of hardware (360 2.93GHz cores, 2.8TB of RAM, 960GB SSD, 40TB disk for one full rack) with excellent InfiniBand connectivity between the nodes. And you can extend the InfiniBand connectivity to other Exalogic and/or Exadata racks. The whole packaged is optimized for the Oracle Fusion Middleware stack (WebLogic, Coherence…) and managed by Oracle Enterprise Manager.

This is really just the start of a long linage of optimized, pre-packaged, simplified (for application administrators and infrastructure administrators) application platforms. Management will play a central role and I am very excited about everything Enterprise Manager can and will bring to it.

If “Exalogic Elastic Cloud” is too taxing to say, you can shorten it to “Exalogic” or even just “EL”. Please, just don’t call it “E2C”. We don’t want to get into a trademark fight with our good friends at Amazon, especially since the next important announcement is…

Run certified Oracle software on OVM at Amazon

Oracle and Amazon have announced that AWS will offer virtual machines that run on top of OVM (Oracle’s hypervisor). Many Oracle products have been certified in this configuration; AMIs will soon be available. There is a joint support process in place between Amazon and Oracle. The virtual machines use hard partitioning and the licensing rules are the same as those that apply if you use OVM and hard partitioning in your own datacenter. You can transfer licenses between AWS and your data center.

One interesting aspect is that there is no extra fee on Amazon’s part for this. Which means that you can run an EC2 VM with Oracle Linux on OVM (an Oracle-tested combination) for the same price (without Oracle Linux support) as some other Linux distribution (also without support) on Amazon’s flavor of Xen. And install any software, including non-Oracle, on this VM. This is not the primary intent of this partnership, but I am curious to see if some people will take advantage of it.

Speaking of Oracle Linux, the next announcement is…

The Unbreakable Enterprise Kernel for Oracle Linux

In addition to the RedHat-compatible kernel that Oracle has been providing for a while (and will keep supporting), Oracle will also offer its own Linux kernel. I am not enough of a Linux geek to get teary-eyed about the birth announcement of a new kernel, but here is why I think this is an important milestone. The stratification of the application runtime stack is largely a relic of the past, when each layer had enough innovation to justify combining them as you see fit. Nowadays, the innovation is not in the hypervisor, in the OS or in the JVM as much as it is in how effectively they all combine. JRockit Virtual Edition is a clear indicator of things to come. Application runtimes will eventually be highly integrated and optimized. No more scheduler on top of a scheduler on top of a scheduler. If you squint, you’ll be able to recognize aspects of a hypervisor here, aspects of an OS there and aspects of a JVM somewhere else. But it will be mostly of interest to historians.

Oracle has by far the most expertise in JVMs and over the years has built a considerable amount of expertise in hypervisors. With the addition of Solaris and this new milestone in Linux access and expertise, what we are seeing is the emergence of a company for which there will be no technical barrier to innovation on making all these pieces work efficiently together. And, unlike many competitors who derive most of their revenues from parts of this infrastructure, no revenue-protection handcuffs hampering innovation either.

Fusion Apps

Larry also talked about Fusion Apps, but I believe he plans to spend more time on this during his Wednesday keynote, so I’ll leave this topic aside for now. Just remember that Enterprise Manager loves Fusion Apps.

And what about Enterprise Manager?

We don’t have many attention-grabbing Enterprise Manager product announcements at Oracle Open World 2010, because we had a big launch of Enterprise Manager 11g earlier this year, in which a lot of new features were released. Technically these are not Oracle Open World news anymore, but many attendees have not seen them yet so we are busy giving demos, hands-on labs and presentations. From an application and middleware perspective, we focus on end-to-end management (e.g. from user experience to BTM to SOA management to Java diagnostic to SQL) for faster resolution, application lifecycle integration (provisioning, configuration management, testing) for lower TCO and unified coverage of all the key parts of the Oracle portfolio for productivity and reliability. We are also sharing some plans and our vision on topics such as application management, Cloud, support integration etc. But in this post, I have chosen to only focus on new product announcements. Things that were not publicly known 48 hours ago. I am also not covering JavaOne (see Alexis). There is just too much going on this week…

Just kidding, we like it this way. And so do the customers I’ve been talking to.

Comments Off on Exalogic, EC2-on-OVM, Oracle Linux: The Oracle Open World early recap

Filed under Amazon, Application Mgmt, Cloud Computing, Conference, Everything, Linux, Manageability, Middleware, Open source, Oracle, Oracle Open World, OVM, Tech, Trade show, Utility computing, Virtualization, Xen

The PaaS Lament: In the Cloud, application administrators should administrate applications

Some organizations just have “systems administrators” in charges of their applications. Others call out an “application administrator” role but it is usually overloaded: it doesn’t separate the application platform administrator from the true application administrator. The first one is in charge of the application runtime infrastructure (e.g. the application server, SOA tools, MDM, IdM, message bus, etc). The second is in charge of the applications themselves (e.g. Java applications and the various artifacts that are used to customize the middleware stack to serve the application).

In effect, I am describing something close to the split between the DBA and the application administrators. The first step is to turn this duo (app admin, DBA) into a triplet (app admin, platform admin, DBA). That would be progress, but such a triplet is not actually what I am really after as it is too strongly tied to a traditional 3-tier architecture. What we really need is a first-order separation between the application administrator and the infrastructure administrators (not the plural). And then, if needed, a second-order split between a handful of different infrastructure administrators, one of which may be a DBA (or a DBA++, having expanded to all data storage services, not just relational), another of which may be an application platform administrator.

There are two reasons for the current unfortunate amalgam of the “application administrator” and “application platform administrator” roles. A bad one and a good one.

The bad reason is a shortcomings of the majority of middleware products. While they generally do a good job on performance, reliability and developer productivity, they generally do a poor job at providing a clean separation of the performance/administration functions that are relevant to the runtime and those that are relevant to the deployed applications. Their usual role definitions are more structured along the lines of what actions you can perform rather than on what entities you can perform them. From a runtime perspective, the applications are not well isolated from one another either, which means that in real life you have to consider the entire system (the middleware and all deployed applications) if you want to make changes in a safe way.

The good reason for the current lack of separation between application administrators and middleware administrators is that middleware products have generally done a good job of supporting development innovation and optimization. Frameworks appear and evolve to respond to the challenges encountered by developers. Knobs and dials are exposed which allow heavy customization of the runtime to meet the performance and feature needs of a specific application. With developers driving what middleware is used and how it is used, it’s a natural consequence that the middleware is managed in tight correlation with how the application is managed.

Just like there is tension between DBAs and the “application people” (application administrators and/or developers), there is an inherent tension in the split I am advocating between application management and application platform management. The tension flows from the previous paragraph (the “good reason” for the current amalgam): a split between application administrators and application platform administrators would have the downside of dampening application platform innovation. Or rather it redirects it, in a mutation not unlike the move from artisans to industry. Rather than focusing on highly-specialized frameworks and highly-tuned runtimes, the application platform innovation is redirected towards the goals of extreme cost efficiency, high reliability, consistent security and scalability-by-default. These become the main objectives of the application platform administrator. In that perspective, the focus of the application architect and the application administrator needs to switch from taking advantage of the customizability of the runtime to optimize local-node performance towards taking advantage of the dynamism of the application platform to optimize for scalability and economy.

Innovation in terms of new frameworks and programming models takes a hit in that model, but there are ways to compensate. The services offered by the platform can be at different levels of generality. The more generic ones can be used to host innovative application frameworks and tools. For example, a highly-specialized service like an identity management system is hard to use for another purpose, but on the other hand a JVM can be used to host not just business applications but also platform-like things like Hadoop. They can run in the “application space” until they are mature enough to be incorporated in the “application platform space” and become the responsibility of the application platform administrator.

The need to keep a door open for innovation is part of why, as much as I believe in PaaS, I don’t think IaaS is going away anytime soon. Not only do we need VMs for backward-looking legacy apps, we also need polyvalent platforms, like a VM, for forward-looking purposes, to allow developers to influence platform innovation, based on their needs and ideas.

Forget the guillotine, maybe I should carry an axe around. That may help get the point across, that I want to slice application administrators in two, head to toe. PaaS is not a question of runtime. It’s a question of administrative roles.

Comments Off on The PaaS Lament: In the Cloud, application administrators should administrate applications

Filed under Application Mgmt, Cloud Computing, Everything, IT Systems Mgmt, Manageability, Mgmt integration, Middleware, PaaS, Utility computing, Virtualization

The necessity of PaaS: Will Microsoft be the Singapore of Cloud Computing?

From ancient Mesopotamia to, more recently, Holland, Switzerland, Japan, Singapore and Korea, the success of many societies has been in part credited to their lack of natural resources. The theory being that it motivated them to rely on human capital, commerce and innovation rather than resource extraction. This approach eventually put them ahead of their better-endowed neighbors.

A similar dynamic may well propel Microsoft ahead in PaaS (Platform as a Service): IaaS with Windows is so painful that it may force Microsoft to focus on PaaS. The motivation is strong to “go up the stack” when the alternative is to cultivate the arid land of Windows-based IaaS.

I should disclose that I work for one of Microsoft’s main competitors, Oracle (though this blog only represents personal opinions), and that I am not an expert Windows system administrator. But I have enough experience to have seen some of the many reasons why Windows feels like a much less IaaS-friendly environment than Linux: e.g. the lack of SSH, the cumbersomeness of RDP, the constraints of the Windows license enforcement system, the Windows update mechanism, the immaturity of scripting, the difficulty of managing Windows from non-Windows machines (despite WS-Management), etc. For a simple illustration, go to EC2 and compare, between a Windows AMI and a Linux AMI, the steps (and time) needed to get from selecting an image to the point where you’re logged in and in control of a VM. And if you think that’s bad, things get even worse when we’re not just talking about a few long-lived Windows server instances in the Cloud but a highly dynamic environment in which all steps have to be automated and repeatable.

I am not saying that there aren’t ways around all this, just like it’s not impossible to grow grapes in Holland. It’s just usually not worth the effort. This recent post by RighScale illustrates both how hard it is but also that it is possible if you’re determined. The question is what benefits you get from Windows guests in IaaS and whether they justify the extra work. And also the additional license fee (while many of the issues are technical, others stem more from Microsoft’s refusal to acknowledge that the OS is a commodity). [Side note: this discussion is about Windows as a guest OS and not about the comparative virtues of Hyper-V, Xen-based hypervisors and VMWare.]

Under the DSI banner, Microsoft has been working for a while on improving the management/automation infrastructure for Windows, with tools like PowerShell (which I like a lot). These efforts pre-date the Cloud wave but definitely help Windows try to hold it own on the IaaS battleground. Still, it’s an uphill battle compared with Linux. So it makes perfect sense for Microsoft to move the battle to PaaS.

Just like commerce and innovation will, in the long term, bring more prosperity than focusing on mining and agriculture, PaaS will, in the long term, yield more benefits than IaaS. Even though it’s harder at first. That’s the good news for Microsoft.

On the other hand, lack of natural resources is not a guarantee of success either (as many poor desertic countries can testify) and Microsoft will have to fight to be successful in PaaS. But the work on Azure and many research efforts, like the “next-generation programming model for the cloud” (codename “Orleans”) that Mary Jo Foley revealed today, indicate that they are taking it very seriously. Their approach is not restricted by a VM-centric vision, which is often tempting for hypervisor and OS vendors. Microsoft’s move to PaaS is also facilitated by the fact that, while system administration and automation may not be a strength, development tools and application platforms are.