The promise of PaaS is that application owners don’t need to worry about the infrastructure that powers the application. They just provide application artifacts (e.g. WAR files) and everything else is taken care of. Backups. Scaling. Infrastructure patching. Network configuration. Geographic distribution. Etc. All these headaches are gone. Just pick from a menu of quality of service options (and the corresponding price list). Make your choice and forget about it.

In theory.

In practice no abstraction is leak-proof and the abstractions provided by PaaS environments are even more porous than average. The first goal of PaaS providers should be to shore them up, in order to deliver on the PaaS value proposition of simplification. But at some point you also have to acknowledge that there are some irreducible leaks and take pragmatic steps to help application administrators deal with them. The worst thing you can do is have application owners suffer from a leaky abstraction and refuse to even acknowledge it because it breaks your nice mental model.

Google App Engine (GAE) gives us a nice and simple example. When you first deploy an application on GAE, it is deployed as just one instance. As traffic increases, a second instance comes up to handle the load. Then a third. If traffic decreases, one instance may disappear. Or one of them may just go away for no reason (that you’re aware of).

It would be nice if you could deploy your application on what looks like a single, infinitely scalable, machine and not ever have to worry about horizontal scale-out. But that’s just not possible (at a reasonable cost) so Google doesn’t try particularly hard to hide the fact that many instances can be involved. You can choose to ignore that fact and your application will still work. But you’ll notice that some requests take a lot more time to complete than others (which is typically the case for the first request to hit a new instance). And some requests will find an empty local cache even though your application has had uninterrupted traffic. If you choose to live with the “one infinitely scalable machine” simplification, these are inexplicable and unpredictable events.

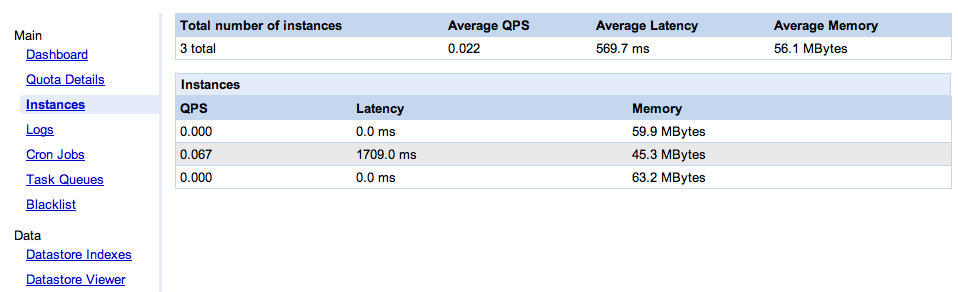

Last week, as part of the release of the GAE SDK 1.3.8, Google went one step further in acknowledging that several instances can serve your application, and helping you deal with it. They now give you a console (pictured below) which shows the instances currently serving your application.

I am very glad that they added this console, because it clearly puts on the table the question of how much your PaaS provider should open the kimono. What’s the right amount of visibility, somewhere between “one infinitely scalable computer” and giving you fan speeds and CPU temperature?

I don’t know what the answer is, but unfortunately I am pretty sure this console is not it. It is supposed to be useful “in debugging your application and also understanding its performance characteristics“. Hmm, how so exactly? Not only is this console very simple, it’s almost useless. Let me enumerate the ways.

Misleading

Actually it’s worse than useless, it’s misleading. As we can see on the screen shot, two of the instances saw no traffic during the collection period (which, BTW, we don’t know the length of), while the third one did all the work. At the top, we see an “average latency” value. Averaging latency across instances is meaningless if you don’t weight it properly. In this case, all the requests went to the instance that had an average latency of 1709ms, but apparently the overall average latency of the application is 569.7ms (yes, that’s 1709/3). Swell.

No instance identification

What happens when the console is refreshed? Maybe there will only be two instances. How do I know which one went away? Or say there are still three, how do I know these are the same three? For all I know it could be one old instance and two new ones. The single most important data point (from the application administrator’s perspective) is when a new instance comes up. I have no way, in this UI, to know reliably when that happens: no instance identification, no indication of the age of an instance.

Average memory

So we get the average memory per instance. What are we supposed to do with that information? What’s a good number, what’s a bad number? How much memory is available? Is my app memory-bound, CPU-bound or IO-bound on this instance?

Configuration management

As I have described before, change and configuration management in a PaaS setting is a thorny problem. This console doesn’t tackle it. Nowhere does it say which version of the GAE platform each instance is running. Google announces GAE SDK releases (the bits you download), but these releases are mostly made of new platform features, so they imply a corresponding update to Google’s servers. That can’t happen instantly, there must be some kind of roll-out (whether the instances can be hot-patched or need to be recycled). Which means that the instances of my application are transitioned from one platform version to another (and presumably that at a given point in time all the instances of my application may not be using the same platform version). Maybe that’s the source of my problem. Wouldn’t it be nice if I knew which platform version an instance runs? Wouldn’t it be nice if my log files included that? Wouldn’t it be nice if I could request an app to run on a specific platform version for debugging purpose? Sure, in theory all the upgrades are backward-compatible, so it “shouldn’t matter”. But as explained above, “the worst thing you can do is have application owners suffer from a leaky abstraction and refuse to even acknowledge it“.

OK, so the instance monitoring console Google just rolled out is seriously lacking. As is too often the case with IT monitoring systems, it reports what is convenient to collect, not what is useful. I’m sure they’ll fix it over time. What this console does well (and really the main point of this blog) is illustrate the challenge of how much information about the underlying infrastructure should be surfaced.

Surface too little and you leave application administrators powerless. Surface more data but no control and you’ll leave them frustrated. Surface some controls (e.g. a way to configure the scaling out strategy) and you’ve taken away some of the PaaS simplicity and also added constraints to your infrastructure management strategy, making it potentially less efficient. If you go down that route, you can end up with the other flavor of PaaS, the IaaS-based PaaS in which you have an automated way to create a deployment but what you hand back to the application administrator is a set of VMs to manage.

That IaaS-centric PaaS is a well-understood beast, to which many existing tools and management practices can be applied. The “pure PaaS” approach pioneered by GAE is much more of a terra incognita from a management perspective. I don’t know, for example, whether exposing the platform version of each instance, as described above, is a good idea. How leaky is the “platform upgrades are always backward-compatible” assumption? Google, and others, are experimenting with the right abstraction level, APIs, tools, and processes to expose to application administrators. That’s how we’ll find out.

Pingback: William Vambenepe — Google, WTF? (What’s The Formula?)