Twitter has decided that for our good and their own it would be better if any time you click a link in a tweet the request first went to Twitter before being redirected to the intended destination. This blog entry announces the decision, but a lot of the interesting details are hidden in the more technical description of the change sent to the Twitter developers mailing list.

Here is a quick analysis of the announcement and its ramifications.

The advertised benefits

For users:

- Twitter scans the links for malware, offering a layer of protection

- It becomes easy to shorten links directly from the Tweet box on twitter.com (or from any client that doesn’t have a built-in link shortening feature)

For Twitter:

- they collect a lot of profiling data on user behavior, which can be used to improve the “Promoted Tweets” system (and possibly plenty of other uses)

You don’t have to be much of a cynic to notice that the user benefits are already available today for those who care about them (get a link scanner on your computer, get a Twitter client with built-in link shortening) while the benefit to Twitter is a brand new and major addition…

One interesting side-effect: the erosion of the 140 character limitation

Without going into the technical details of the new system, one change is that each URL will now “cost” 20 characters (out of the 140 allowed per tweet), no matter how long it really is. But in most cases the user will still see the complete URL in the tweet (clients may choose to display something else but I doubt they will, at least by default, except for SMS). So you could now see tweets like (line breaks added):

In the town where I was born / Lived a man who sailed to sea /

And he told us of his life / In the land of submarines, http://more.com/

So.we.sailed.on.to.the.sun/Till.we.found.the.sea.green/

And.we.lived.beneath.the.waves/In.our.yellow.submarine/

We.all.live.in.yellow.submarine/Yellow.submarine,yellow.submarine/

We.all.live in.yellow.submarine/Yellow.submarine,yellow.submarine.

Based on the Twitter proposal, clicking on this link would send you to a Twitter-operated link shortener (e.g. http://t.co/J7erFi3) which would then redirect you to the full URL above. The site (e.g. more.com in this example) could be trivially set up so that such URLs are all valid and they return a clean version of the encoded text (for the benefit of users of Twitter clients that may not show the full URL).

This long URL example may seem a bit overkill (just post 3 tweets), but if you are only short by 20 or 30 characters and just can’t find another way to shorten the tweet the temptation will be big to take this easy escape.

A cool new URL shortening domain

You may have noticed the t.co domain in the previous paragraph. Yes, it’s a real one. That’s the hard-to-beat domain that Twitter was able to score for this. Cute. But frankly I am tired of the whole URL shortening deal and these short domain names have stopped to amuse me. You?

Enforcement

How, you may wonder, can Twitter ensure that the clicks go through its gateway if the full URL is available as part of the Tweet? Simple: they change the terms of service to forbid doing otherwise. It’s interesting how the paragraph in the email to developers which announces that aspect starts by asking nicely “we really do hope that…”, “please send the user through the t.co link”, “please still send him or her through t.co” and ends with a more constraining “we will be updating the TOS to require you to check t.co and register the click”. Speak softly and carry a big stick.

It will be obviously easy to avoid this, and you won’t have to resort top copy/pasting URLs. Even if the client developers play ball, open source clients can be recompiled. Proxies can be put in front of clients to remember the mapping and do the substitution without ever hitting t.co. Plug-ins and Greasemonkey scripts can be developed. Etc. Twitter knows that for sure and probably doesn’t care. As long as by default most users go through t.co the company will get the metrics it needs. It’s actually to Twitter’s benefit to make it easy enough (but not too easy) to circumvent this, as it ensure that those who care will find a solution and therefore keep using the service without too much of a fuss. We can’t tell you to cheat but we’ll hint that we don’t mind if you do.

The privacy angle

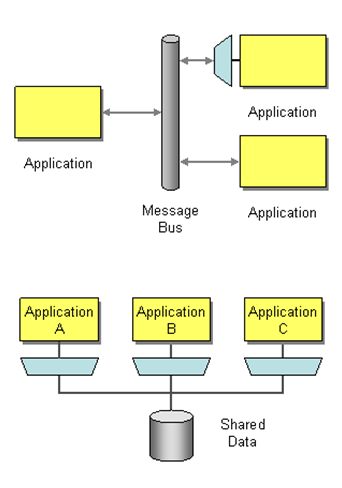

This is a big deal, and disappointing to me. Obviously the hopes I had for Twitter to become the backbone of an open, user-controlled, social data bus are not shared by its management. Until now, Twitter was a good citizen in a world of privacy-violating social networks because the data it shared (your tweets and your basic profile data) had always and unambiguously been expected to be public. Not true with your click stream. An average user will have no idea that when he clicks on http://cnn.com/some.story the request first goes to Twitter. Twitter now has access to identified personal data (the click stream) that its users do not mean to share. I realize that this is old news in a world of syndicated web advertising and centralized analytics, but this is new for Twitter and now puts them in position to mishandle this data, purposely or not, in the way they store it, use it and share it.

I wouldn’t be surprised if they end up forced to offer an option to not go through t.co and they had additional metadata in the user profile to inform the Twitter client that it is OK for this user not to go through the gateway when they click on a link. We’ll see.

The impact on the Twitter application ecosystem

The assault on URL shorteners was expected since the Chirp conference (and even before). Most Twitter application developers had already swallowed the “if you just fill a hole in the platform we’ll eventually crush you” message. What’s new in this announcement is that it also shows that Twitter is willing to use its Terms of Service document as a competitive tool, just like Steve Jobs does with Flash. Not unexpected, but it wasn’t quite as clear before.

It’s not a pretty implementation

Here is what it looks like at the API level: the actual tweet text contains the t.co shortened URL. And for each such URL there is a piece of metadata that gives you the t.co URL, the corresponding full-length URL (which you should display instead of the t.co one) and the begin/end character position of the t.co URL in the original tweet so you can easily pull it out (not sure why you need the end position since it’s always beginning+20 but serialized Twitter message are already happily duplicative).

As a modeling and serialization geek, I am not impressed by the technical approach taken here. But before I flame Twitter I should acknowledge the obvious: that the Twitter API has seen a rate of adoption several orders of magnitude larger than any protocol I had anything to do with. Still, it would take more than this detail of history to prevent me from pontificating.

For such a young company, the payload of a Twitter message is already quite a mess, mixing duplications, backward-compatible band-aids, real technical constraints and self-imposed constraints. Why, pray tell, do we even need to shorten URLs? If you’re an outsider forced to live within the constraints of the Twitter rules (chiefly, the 140 character limit), they make sense. But if you’re Twitter itself? With the amount of cruft and repetition in a serialized Twitter message, don’t tell me these characters actually matter on the wire. I know they do for SMS, but then just shorten the links in tweets sent over SMS. In the other cases, it reminds me of the frustrating experience of being told by the owner of a Mom-and-Pop store that they can’t accede to your demand because of “company policy”.

Isn’t it time for the text of tweets to contain real markup so that rather than staring at a URL we see highlighted words that point somewhere? Just like… any web page. Isn’t it the easiest for an application to process and doesn’t it offer the reader a more fluid text (Gillmor and Carr notwithstanding)? By now, isn’t this how people are used to consuming hypertext?

Couldn’t the backward compatibility issue of such an approach be solved simply by allowing client applications to specify in their Twitter registration settings that yes, they are able to handle such earth-shattering concept as a <a href=””></a> element. This doesn’t prevent a URL to “cost” you some fixed number of characters, it doesn’t prevent the use of a tracker/filter gateway if that’s your business decision.

We’ll see how users (and application developers) react to this change. As fans of Douglas Adams know, the risk of claiming that “all your click are belong to us” is that you expose yourself to hearing “so long, and thanks for all the whale” as an answer…